James Dean: What Makes a Film Icon?

In this essay, I discuss the ontology of star iconicity, taking James Dean (and the rebel icon) as a case study to explore this concept.

The concept of iconicity is an ancient one. Its contemplation extends back to Platonic philosophy (Meir and Tkachman). Contemporarily, the concept is considered from within the intertwined fields of linguistics and semiotics. Irit Meir and Oksana Tkachman describe iconicity as ‘a relationship of resemblance’ between the form of a sign, the signifier, and its meaning, the signified. Necessarily, when a sign is iconic, there is a close correlation between its form and meaning (Meir and Tkachman). For example, a triangular road sign depicting a deer graphic warns drivers of the animal’s possible presence in a certain area: the form and meaning of the sign are closely related. Not all signs are iconic, however. When the sign bears no resemblance to the signified, the sign is said to be based on ‘convention’, and thus the association between form and meaning is ‘arbitrary’ (Meir and Tkachman). The sign of a currency, such as the dollar sign ($), is an example of an arbitrary sign. In both cases, the ontology of the sign is predicated on the relationship between form and meaning. A close relationship indicates iconicity, and a distinct relationship indicates arbitrariness, with both existing in degrees of intensity. A photograph of an apple, for instance, displays a higher degree of iconicity than a drawing of one. Naturally, mediums containing a photographic basis, such as cinema, are ontologically iconic.

Cinema is also able to produce an alternative, ideological, type of iconicity: the star icon. Here, the correlation between form and meaning is simultaneously patent yet difficult to parse. This is because a human being, in all their complexity, becomes the signifier of a universal meaning––often, an archetype of some ideal––that is abstract and mystical, and thus evades definition (Springer 16 –19). The star becomes an icon by virtue of a wide array of attributes (such as, their physiognomy, gesture, dress, and disposition) that are all enmeshed in their filmic, extra-filmic, and paratextual personas (Springer 19). Altogether, this amalgamation provides ‘a form around which fans’ inchoate inner lives can cohere’, something that they can adore through projection (Springer 18 – 19). Indeed, as an object, Marshall Fishwick writes, the pop icon inflames the same ‘level of love and reverence’ as the more typical icons of religious significance, such as the Virgin Mary (3 – 4). There are many stars of the screen (and sound), but very few are truly iconic. Of the 20th Century, three individuals stand out: Marilyn Monroe, the sex icon; Elvis Presley, the rock-and-roll icon; and James Dean, the rebel icon.

This essay will take Dean as a case study to explore the concept of iconicity as the brevity of his career, and his untimely death by car crash, has allowed a particularly potent distillation of those qualities he has come to iconise: disaffected youth, social estrangement, and the angst-driven desire to rebel against the generational divide. In his short life, Dean only made three feature films––East of Eden (Elia Kazan, 1955), Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955), and Giant (George Stevens, 1956), with the latter two released posthumously––but this only catalysed his legend. To anchor this conceptual exploration, I will consider the perplexing transparency and opacity of iconicity as it manifests ideologically, and is fortified ontologically, in and by cinema.

I. Star Iconicity: A Scholarly Sketch

Star iconicity represents an interesting intersection between film semiotics [1] and star studies, a bountiful subfield of film studies. However, in both areas, the concept of iconicity remains a marginal topic of study. Stephen Prince observes that film theory since the 1970s has been greatly influenced by ‘structuralist and Saussurean-derived linguistic models’, with current film theory extending from the semiotic lineage of works by Ferdinand de Saussaure, Louis Althusser, and Jacques Lacan (16).

Prince continues to posit: ‘Like books, films are regarded as texts for reading by viewers or critics, with the concomitant implication that such reading activates similar processes of semiotic decoding’ (16). What is more, Prince notes that despite this focus on cinematic signification, the overwhelming emphasis has been placed on the arbitrary and symbolic nature between the signifier and the signified, displacing ‘an appreciation of the iconic and mimetic aspect of certain categories of signs, namely pictorial signs, those most relevant to an understanding of the cinema’ (16).

Meanwhile, the field of star studies, as Richard Dyer surveys, has been traditionally dominated by two distinct methodological approaches in the reading of stars in films: sociological and semiotic (1). Dyer’s seminal text, Stars, provides a distilled confluence of both views––the star as social phenomenon, and the star as sign within the filmic text––arguing for the interdependence of these two approaches (1). Paul McDonald identifies the notion of the ‘star image’ as the key contribution of Dyer’s study (176). This notion not only accounts for the films within which stars feature, but also the wide array of media surrounding and informing the formation of their star personas: magazines, posters, newspaper articles, and so on (Dyer 1). Gérard Genette would call this accompanying media, or rather ‘accompanying productions’, the paratexts of a film, a term he initially coined in relation to literary works, but a phenomenon that is certainly observable in cinema too (1). Paratexts, as Cornelia Klecker writes, ‘resemble thresholds rather than borders since they build a zone of transition and transaction, a place to influence reception’ (402). In this brief elaboration, we can already see the utility of paratexts in the formation of star iconicity; they serve an integral role in shaping the public image of stars, and can reinforce qualities that they come to be associated with.

Still, within the relatively broad field of star studies, iconicity itself is less discussed. When these discussions do take place, iconicity tends to be treated not only as symptomatic of the media circus surrounding the silver screen, but also of the wider Zeitgeist. Indeed, studies that recognise the iconicity of certain stars, such as Dean, often do so as a conduit to comment on broader cultural hermeneutics. For instance, in James Dean Transfigured: The Many Faces of Rebel Iconography, Claudia Springer adopts a culturalist methodology to locate the origins of the rebel icon within the socio-historical milieu of 1950s America, and its appropriations thereafter across the globe, contextualising each reuse as she does. Springer takes Dean as a prominent figure in the advent of the rebel icon, but places most of her critical emphasis on external factors, such as:

‘an emerging consumer culture in an affluent postwar society; a repressive social climate of homophobia, misogyny, racism, and anti-youth rhetoric; the appropriation of a black style by disaffected young white people looking for a defiant stance; the conventions introduced by Hollywood’s teen films; and media and studio manipulation of James Dean’s public image’ (3).

The study of star iconicity as a cultural, social and industrial phenomenon is valuable in its contextualisation of the emergence of certain icons. In collaboration with this sociological approach, what follows is an analysis of how the ontology of the cinematic medium itself contributes to the creation of star icons, namely the rebel archetype.

II. The Rebel Icon

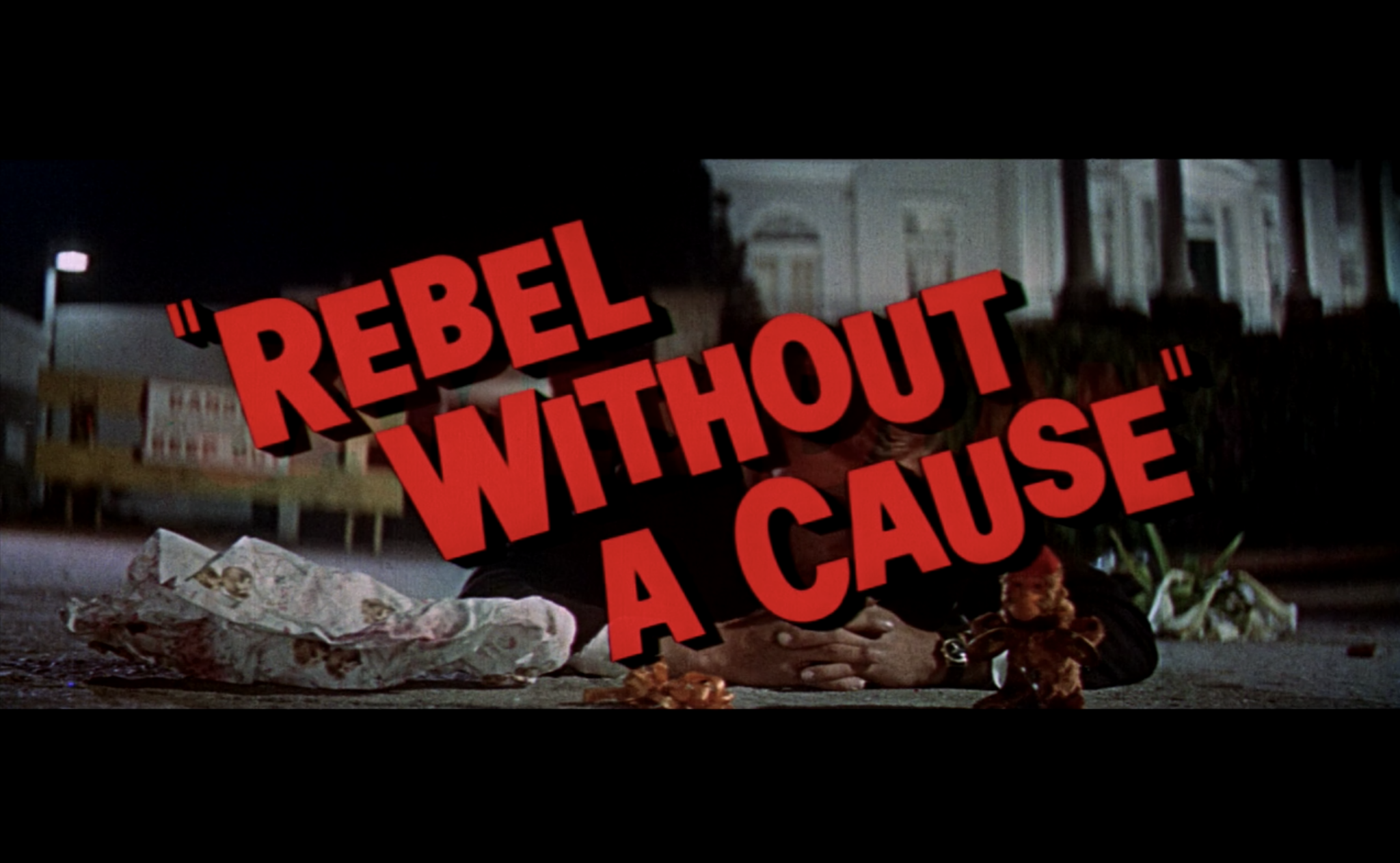

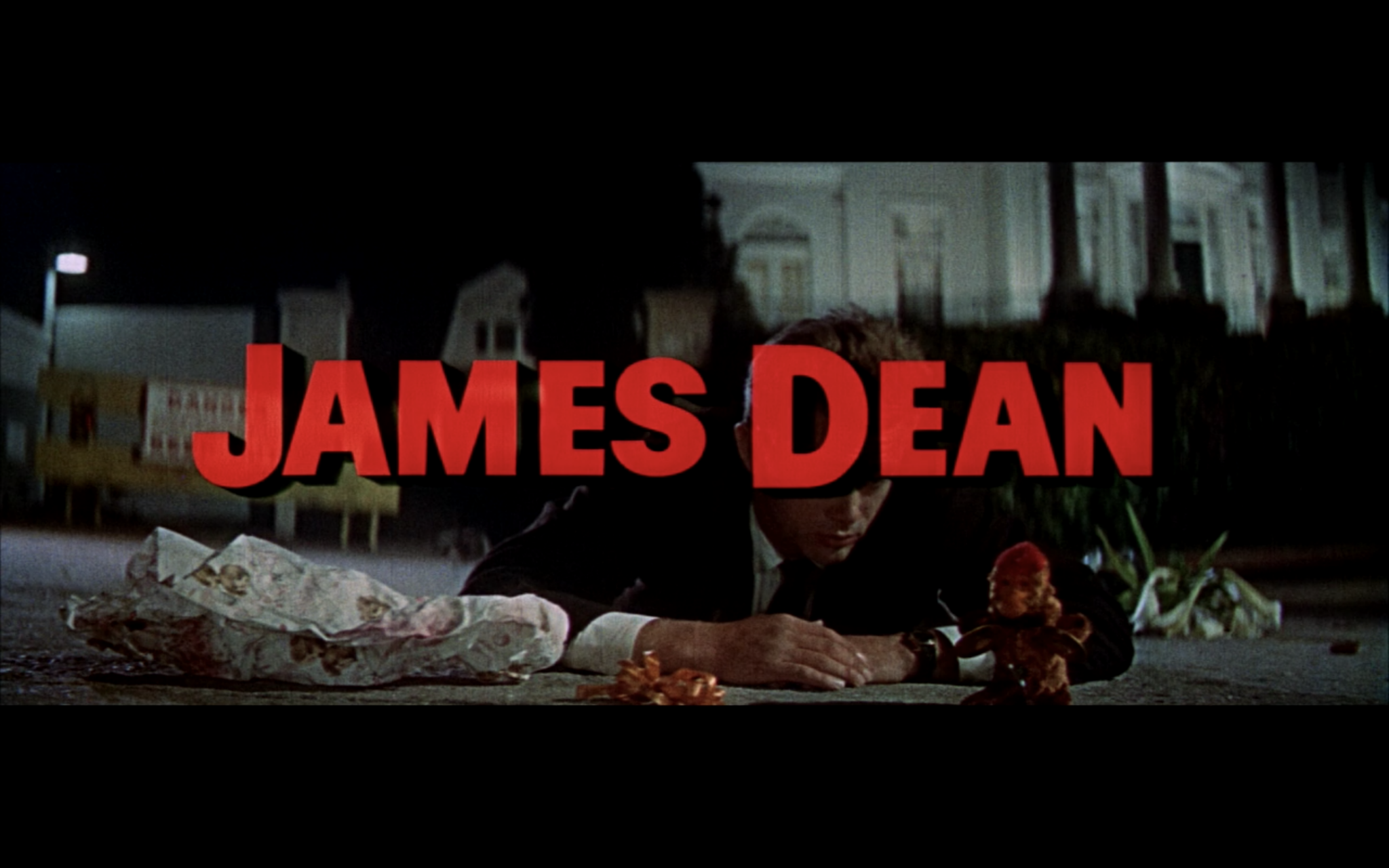

As we shall see, the rebel icon is particularly difficult to delineate, especially as embodied by an actor as volatile as Dean. Further still, the elusiveness of the rebel icon is exacerbated by its apolitical ontology. Paradoxically, Dean’s rebellious characters do not appear to uphold any overtly oppositional political views, an observation that Springer attributes to the ‘censorious climate of the fifties’ (32). This wayward indifference is epitomised by Dean’s most celebrated film, Rebel Without a Cause––the telling title blazoned in Technicolor red in an ironic show of bravado across the opening shot, wherein Dean as Jim Stark lies intoxicated on the street as he tucks a toy monkey to bed with a piece of rubbish (Figs. 1 – 3). The typography of the title is tilted and cartoonish as if to mock the plight of Stark (and the generation he represents) whose rebellion largely stems from the internal failings of his familial unit––an overbearing mother, and an emasculated father––and manifests in these moments of self-destructive behaviour.

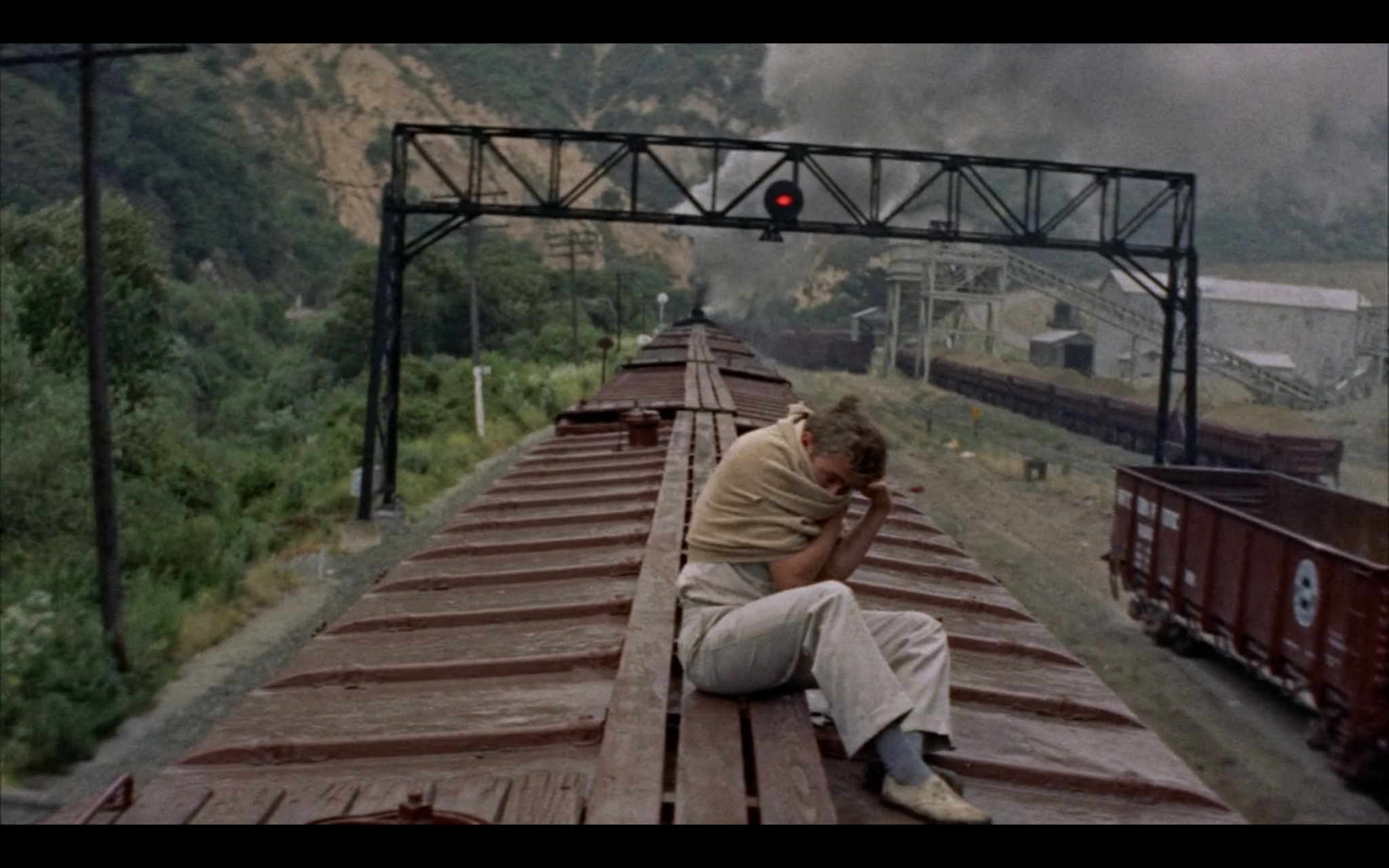

A comparable dynamic of familial frustration also occupies Dean’s role in his stunning feature film debut, East of Eden. He plays the role of Cal Trask, the unfavoured son of two vying for the attention of their reticent father: a modern retelling of the biblical story of Cain and Abel. In this film, Dean similarly expresses his frustration with inadequate parental figures––this time, a distant father, and an absent (brothel-running) mother––through unpredictable (and often improvised) behaviour such as foetal physical contortions (Fig. 5), wild displays of showmanship, and emotional outbursts (Fig. 4). Dyer succinctly summarises these core issues fuelling the troubled psychology of Dean’s first two feature film roles: ‘In Rebel he has too weak a father, in Eden too charismatic a mother’ (54). But, we can in fact observe this dynamic––the unruly externalisation of internal turmoil––in all three of Dean’s films. Springer notes that, although Giant deviates from Dean’s first two films of teenage angst by being an epic Western drama, it manages to substitute ‘authority figures for biological fathers’ (15). Giant spans several decades, with Dean playing ranch hand turned oil tycoon, Jett Rink, opposite Rock Hudson who plays his boss turned business rival, Jordan Benedict. As Rink, Dean leads an equally agonising life of self-destruction, largely in the form of alcoholism and social ineptness, despite his eventual material success.

Viscerally, Dean often oscillates through a kaleidoscope of emotions within a single film. Intrepid and charismatic quickly turns into sullen and taciturn, observable in the fairground brawl sequence of East of Eden, in a brilliant animalism that imbues the rebel icon with an ineffable volatility. The affinity between Dean’s rebellious fluidity and his amorphous characters is exactly what floats his image in the marketplace of universal reception, projection, and reconstitution. The correlation between Dean and his characters cannot be stressed enough for, as David Halberstam observes, all three roles reveal an actor ‘driven by his own pain and anguish’ (1387). This is a salient dimension of Dean’s iconicity, to which I will now turn.

III. The Transparency and Opacity of the Icon

Transparency and opacity are two notions that are closely wedded in the ontology of the icon, a tension succinctly parsed by David Gerald Orr: ‘Icons are the most significant and ambivalently, the most unintelligible of images’ (13). In other words, the icon is transparent in its mode of direct signification, but this transparency comes with an opportunity cost of any other divergent meaning, rendering the icon opaque in the fixation of its signification. This dilemma instils the star icon with a constitutional honesty by virtue of those features made transparent, but with this direct denotation arises an evasive inaccessibility. For instance, using the simplified example of the iconic deer road sign, we can see that it is only able to signify what it iconises––that there are deer within the general proximity––any meaning beyond this is cast aside. Such is the case with the star icon, whose very being is essentialised in signification in such a way that provides no other associative recourse.

The paratexts of a film play an important role in this essentialisation. They can reinforce any iconic signification that an individual may have by facilitating a conference of transparency between character, actor, and star. The relationship between these three personas is an important one to consider in the discussion of iconicity. This is because the degree to which these three faces are interwoven in a star’s public image is often implicated in their ability to transition from mere fame and stardom to immortal enshrinement as an icon. The latter is a particularly porous tripartite persona, a thorough enmeshment of character, actor, and star. Many commentators, such as Halberstam, have noted how indivisible Dean’s life and art were (1387). It goes without saying that Dean’s death––by car accident, no less––at the young age of twenty-four played an indelible role in the formation of his iconicity. Effectively, the tragic event imbued his posthumously released films with an element of prophecy. There is a curious parallel between prophecy and iconicity that accounts for the transparency of the latter. A prophecy is a foreshadowing of a future event, the prediction that something will happen in a certain way. When a prophecy comes true, there is a direct resemblance between the event that occurs and the initial prognosis. As such, a prophecy is a transparent mode of communication. This process also describes iconicity, wherein the iconic sign forewarns its signified meaning with a similar transparency.

In this sense, the nature and prematurity of Dean’s death (his extra-fictional persona) portended, in a mode of iconic signification, the ill-fated essence of his posthumous roles. This cinematic affirmation gave way to the iconicity of the tortured actor. Dean needed to die in actuality in order to be reborn in virtuality. François Truffaut’s essay, “James Dean is Dead”, forms an important document of the historical film critic and viewer, one that captures the realisation of Dean’s seemingly destined iconic becoming:

‘The news, which we learned in Paris the next day, did not arouse much emotion at the time. A young actor, twenty-four years old, was dead. Six months have passed and two of his films have appeared, and now we realize what we have lost…It was his fate to die before his time, as have so many artists’ (296 – 297).

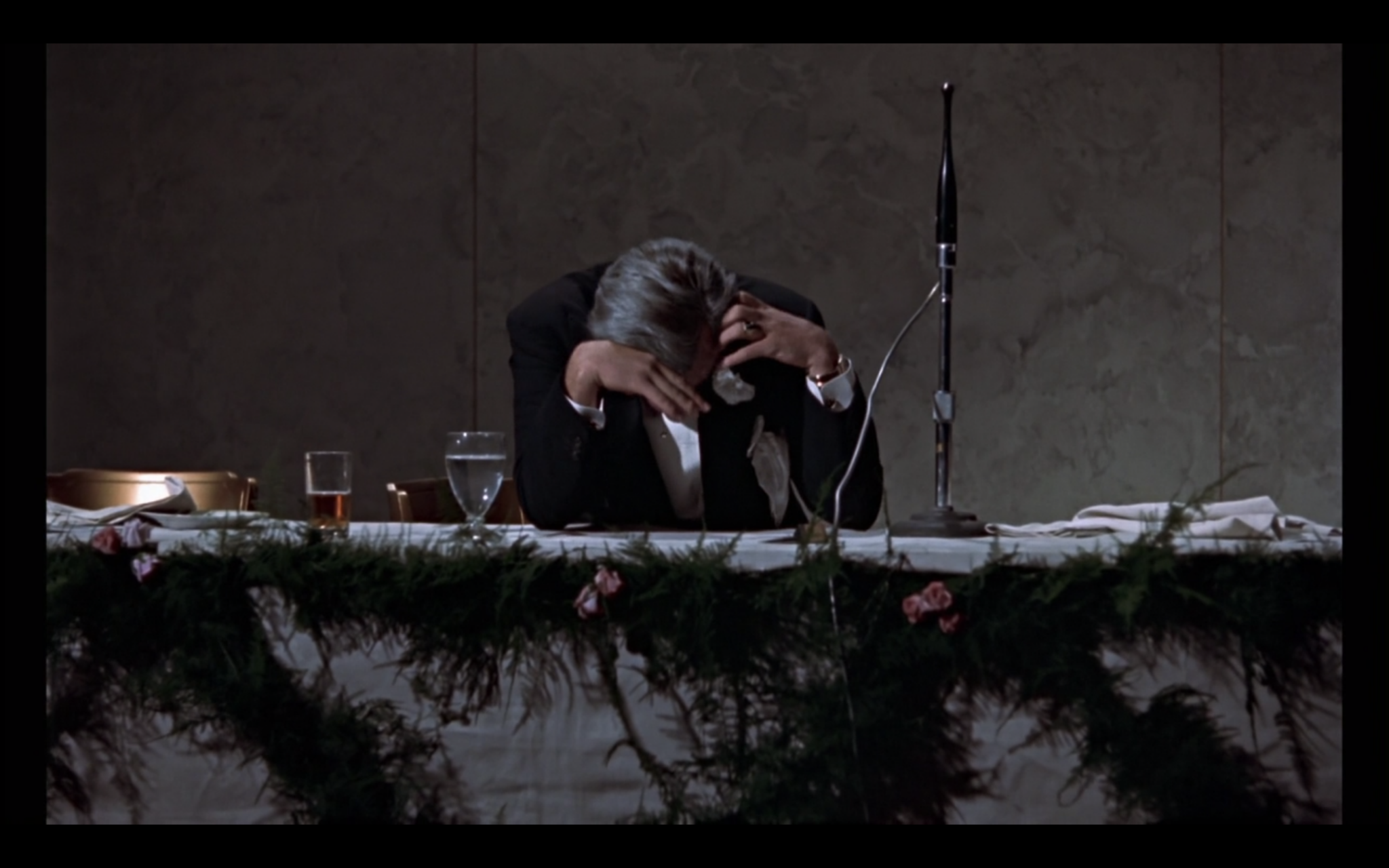

Not even a month had elapsed since the tragic news broke when a mourning audience gathered to watch Dean don that red Harrington jacket in Rebel Without a Cause for the first time. Though, the film’s haunting scenes of bitter irony provide no consolation: ‘Jimmy, you’re very young, a foolish decision now could wreck your whole life. In ten years, you’ll never know this even happened!’, Mrs Stark pleas to her son’s future self, as if possessing a morbid knowing of what had just happened. Whereas, in Giant, we are left with the final image of Dean as Rink aged artificially (the only way of seeing him so) attending a gala held in his own honour as a successful businessman, to which he is physically present but, on account of his intoxication, cognitively absent (Figs. 6 – 7). This unintentional swan song not only echoes Dean’s iconic existence embalmed by celluloid and critical acclaim, but also his ignorance of the proliferation and celebration of this posthumous existence. The greatest cruelty is that although Dean plays doomed characters, they all survive despite the worst odds. Now, all that remains is his tormented image immortalised in a loop: a virtual corpse.

But the correlation between life and art does not stop there. Like his characters, Dean had his own struggles within the familial unit. Many of Dean’s biographers identify the early loss of his mother, and estranged relationship with his father, as ‘the primary causes of his adult moodiness and recklessness’ (Springer 13). This observation can be extended to account for his particularly mercurial performances––a far cry from the still, stable, and secure profile of the leading males of classical Hollywood, as perfectly epitomised by Dean’s Giant co-star, Rock Hudson (Springer 35). Dean readily taps the wellspring of emotional frustration sedimented by his early childhood traumas, and ensuing adult shortcomings, to deliver particularly cathartic performances. Whether this be a desperately improvised embrace of an unloving father, as in East of Eden; an anguished outcry, ‘You’re tearing me apart!’, directed at the incompetent parents of Rebel Without a Cause; or the frenzied defiance, fuelled by striking oil, hurled in the face of a former superior in Giant. Dean paradoxically graces the screen with a transparency of visceral and emotional rebellion that is, all the while, opaque in its ubiquity––such is the conundrum of the icon.

IV. The Ontology of the Screen Performer

The ontology of the screen performer fortifies this perplexity. Appropriately, in The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film, Stanley Cavell dedicates a chapter to the deliberation of this ontological topic, and how it relates to the cinema audience. In this chapter, Cavell distinguishes the screen performer from that of the theatre, identifying the inevitable: ‘movies allow the audience to be mechanically absent’ (25). Yet, as André Bazin avers, this does not mean that ‘the screen is incapable of putting us “in the presence of” the actor’ (97). Although it is undeniable that the real actor is absent, Bazin writes that the screen relays their presence to us via the mirrors of the camera instead (97). Cavell recognises this perplexing presence and absence of cinema’s ontology, and how it uniquely implicates the screen performer:

‘The actor’s role is his subject for study, and there is no end to it. But the screen performer is essentially not an actor at all: he is the subject of study, and a study not his own. (That is what the content of a photograph is––its subject.) On a screen the study is projected; on a stage the actor is the projector’ (28).

In cinema, unlike representational mediums such as painting, there is a collapse that occurs in the interval between the object of the film image itself and the subject that it captures. Another form of transparency and opacity occurs here that speaks to the inherent ontological iconicity of cinema. The photographic basis of cinema extends beyond a mere resemblance or representation of reality, it presents this reality to us, and is in this sense transparent. The opacity of the medium reveals itself through the mediation of the screen and camera, both of which facilitate the proscription of the viewer from the film world, and establish a predetermined inaccessibility despite its transparent presentation.

However, this ontological iconicity does not deem all screen performers iconic in the ideological sense described in this essay, as knowledge of their extra-filmic reality often contends with their fictional, yet pictorially iconic, presence in films. Thus, when faced with a star like Dean––who displays a tightly wound conference between character, actor, and star––the ontological iconicity of cinema gives way to the calcification of their ideological iconicity, and the subsequent essentialisation of the screen performer.

Patently, we have seen that the transparency and opacity of the star icon work in tandem at several levels. The implication for the screen performer is universal in reach, for as Cavell contends: ‘Occasionally the humanity behind the role would manifest itself; and the result was a revelation not of a human individuality, but of an entire realm of humanity becoming visible’ (33 – 34). Ultimately, this twofold iconic fortification presents an ideal star image primed for eternal reconstitution and adoration.

Video

Below you can find the video version of this essay. Alternatively, you can also watch this video, along with others on similar topics, at the Cinema Scholar YouTube channel.

Notes

[1] Robert Stam notes the semiotic turn in film studies, and its indication ‘of a more widespread “linguistic turn”’ (109).

References

· Bazin, André. What is Cinema? Vol. 1. Translated by Hugh Gray, U of California P, 2005.

· Cavell, Stanley. The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film. Harvard UP, 1979.

· Dyer, Richard. Stars. New ed. with a supplementary chapter and bibliography by Paul McDonald, BFI, 1998.

· Fishwick, Marshall. “Icons of America.” Introduction. Icons of America, edited by Ray B. Browne and Marshall Fishwick, Popular Press, 1978, pp. 3 – 12.

· Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Translated by Jane E. Lewin, Cambridge UP, 1997.

· Halberstam, David. The Fifties. ePub ed., Open Road Integrated Media, 2012.

· Klecker, Cornelia. “The other kind of film frames: a research report on paratexts in film.” Word & Image, vol. 31, no. 4, 2015, pp. 402 – 413.

· McDonald, Paul. Supplementary Chapter. “Reconceptualising Stardom.” Stars, by Richard Dyer, BFI, 1998, pp. 175 – 200.

· Meir, Irit and Oksana Tkachman. “Iconicity.” Oxford Bibliographies in “Linguistics”. Oxford UP, last modified 24 March 2014, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199772810/obo-9780199772810-0182.xml

· Orr, David Gerald. “The Icon in the Time Tunnel.” Icons of America, edited by Ray B. Browne and Marshall Fishwick, Popular Press, 1978, pp. 13 – 23.

· Prince, Stephen. “The Discourse of Pictures: Iconicity and Film Studies.” Film Quarterly, vol. 47, no. 1, 1993, pp. 16 – 28.

· Springer, Claudia. James Dean Transfigured: The Many Faces of Rebel Iconography. U of Texas P, 2007.

· Stam, Robert. “Film and Language: From Metz to Bakhtin.” Studies in the Literary Imagination, vol. 19, no.1, 1986, pp. 109 – 130.

· Truffaut, François. “James Dean is Dead.” The Films in My Life, translated by Leonard Mayhew, Simon & Schuster, 1985, pp. 296 – 299.