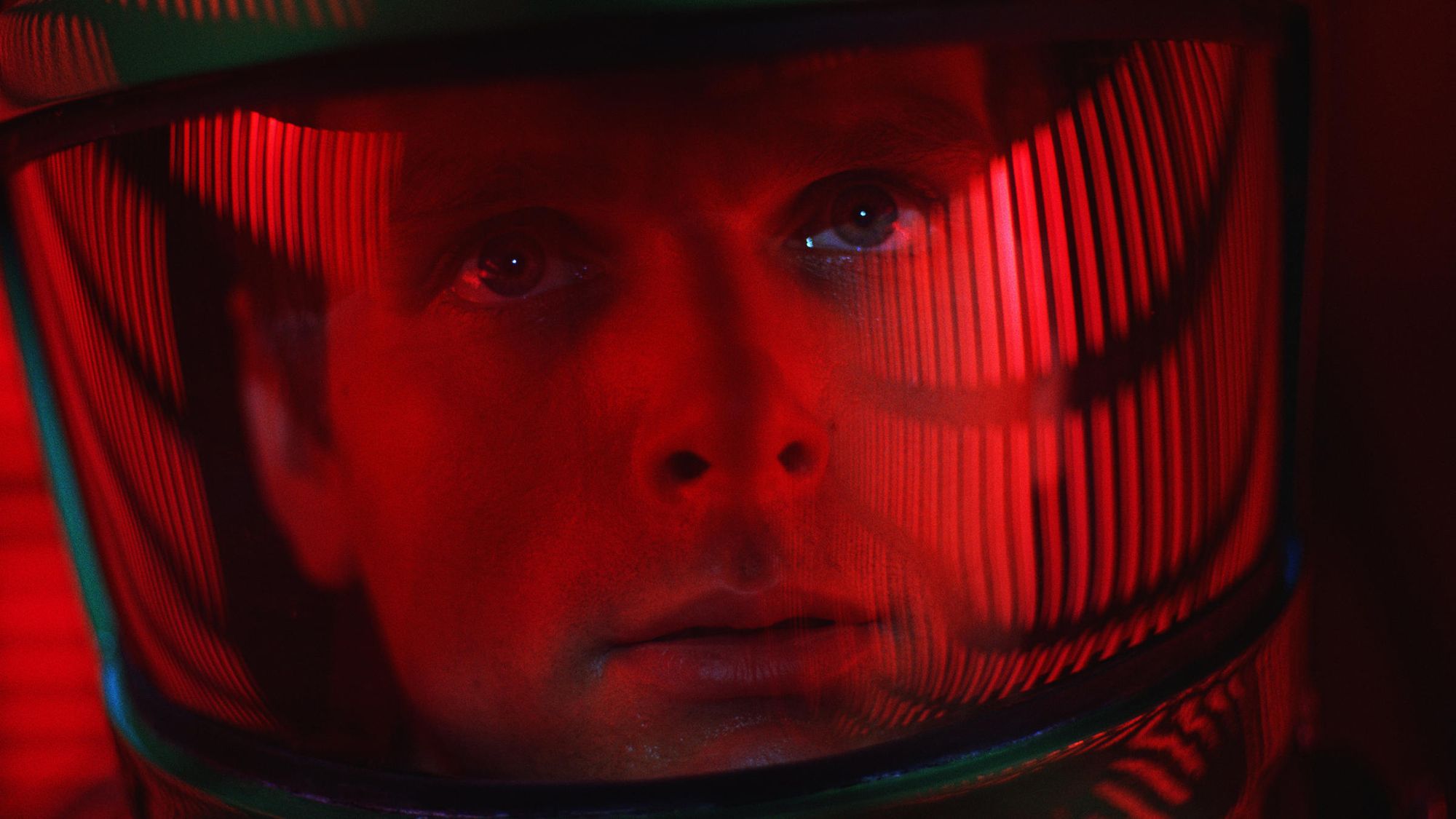

What is Film Aesthetics?

This article seeks to introduce what the academic study of film aesthetics entails.

This article is part one of a two-part series that seeks to introduce what the academic study of film aesthetics entails. However, before broaching this topic, it’s important to establish 1] what the academic discipline of film studies involves more broadly, and 2] what the study of aesthetics entails as a branch of philosophy. Fortunately, I’ve already covered the former in a video essay and article titled, “What is Film Studies?”, which I would recommend watching or reading first before continuing with this article. You can read the article here. The video essay is available to view now on the Cinema Scholar YouTube channel and, for those interested, I’ve embedded a link to it below:

This brings us to the second point that must be established:

What is Aesthetics?

You will often come across broad definitions of aesthetics, such as "the philosophical inquiry into art and beauty", or something to that effect (Pappas). However, as Andrew Klevan points out, “The concept of the ‘aesthetic’ is best considered as a cluster of interrelated meanings” (17). Although, the notion of contemplating art and beauty extends as far back as ancient Greece, the word aesthetics first began being used in the 18th century, when aesthetics emerged as a distinct and systematic strand of Western philosophy (Lamarque). Since then, the term aesthetic has become an allusive and multifaceted one.

Indeed, James Shelley writes that “the term ‘aesthetic’ has come to be used to designate, among other things, a kind of object, a kind of judgment, a kind of attitude, a kind of experience, and a kind of value”. He later elaborates:

[for] the most part, aesthetic theories have divided over questions particular to one or another of these designations: whether artworks are necessarily aesthetic objects; how to square the allegedly perceptual basis of aesthetic judgments with the fact that we give reasons in support of them; how best to capture the elusive contrast between an aesthetic attitude and a practical one; whether to define aesthetic experience according to its phenomenological or representational content; how best to understand the relation between aesthetic value and aesthetic experience. (Shelley)

To complicate matters further, aesthetic inquiries are not limited to artworks; they can be directed towards any object that is perceptible in some way, whether that be furniture, a landscape, or a piece of music. Further to this, the aesthetic does not exclude subject matter that may otherwise be considered ugly, obscene, or unsavoury (Klevan, 19-20). One can, for instance, evaluate the aesthetics of a prison, a cemetery, or a morgue.

Sometimes the philosophical subfield, ‘Philosophy of Art’, is encompassed within aesthetics. Necessarily, this broadens the scope of aesthetics even further to include topics such as, “ontology, definitions of art, spectatorship, and the characteristics of fiction” (Klevan, 20). If we focus, however, on the 18thcentury understanding of aesthetics, the term begins to take on more definition by implicating an expressly evaluative component. As Klevan elaborates:

the interest in aesthetics that emerges in the eighteenth century is explicitly concerned with matters of value, and in particular the judgement of beauty… For Alexander Baumgarten (1714–62) the field of aesthetics would provide a foundation for explaining, and justifying, human judgement about what is and what is not beautiful. (17)

As we shall see, the multifaceted nature of aesthetics can especially be observed in discussions on film, a medium with an ontology ever in flux and its artistic merits constantly weighed.

What is Film Aesthetics?

Perhaps because the advent of film was born out of technological innovation, rather than artistic ambition, early discussions surrounding the new medium were preoccupied by the question of whether or not film should be considered an artform and, if so, what its constituent elements were. In this way, you will find that seminal writings on film are often infused with an awareness of this ontological ambiguity, even if explication of this topic is not the primary goal. This is in part why film aesthetics, as a subfield of film studies, is difficult to define. Matthew Noble-Olson touches on this issue when he writes:

the differentiation of an aesthetic of film from film theory or film philosophy…is complicated, overlapping, and often contested. What might be understood as an aesthetic of film extends back almost to the origins of the medium, and much of what we identify as film theory could be understood as having some aesthetic concern, either as a consideration of film as an art or as a part of the realm of the sensible or the beautiful.

Both of these approaches to film––the discussion of the medium’s ontology and an evaluation of a film’s artistic merits (or demerits)––would fall within the realms of film aesthetics. But, one might then ask, how do these discussions intersect with the non-formal content of a film (e.g. themes or subject matter) or the context of its production? To answer that question, one must first bear in mind that there are various approaches that can be taken in the academic study of film. The most common include: historical, political, industrial, cultural, and philosophical. Within a philosophical outlook, there again exist various strands of focus, one of which is aesthetics. That being said, all of these approaches can, and often do, overlap. Klevan elaborates on this potential and how it implicates a chiefly aesthetic evaluation of film:

Aesthetics does not discount or demean moral, political, emotional, cognitive, or conceptual content. This content is important, and often essential to an aesthetic evaluation, but the engagement will be with the value of its expression through the form of the work. This contrasts with those occasions where, for example, ideological, contextual or conceptual content, even if it relates to formal or presentational matters, is the primary concern and the basis of the evaluation. Equally, not all values relating to the visual, aural, and sensory, the features ostensibly underpinning aesthetic interest, are automatically of aesthetic value. Something may be visually, aurally, and sensually valuable to some of us at some time for some reason – pornography would be an extreme example– and be of little aesthetic value. (20)

Notably, Klevan also cautions:

It is important not to fall prey to a popular misconception… that aesthetics is equivalent to Formalism: an adherence to form at the expense of content (for example, subject matter). Nor is it equivalent to Aestheticism if this is taken to mean an exaggerated devotion to beautiful forms, once again at the expense of content. (20)

As we have seen, then, film aesthetics is a nuanced subfield of film studies. Indeed, an aesthetic study of film can be approached in various ways, and can implicate ideas beyond immediate aesthetic interests. This is reflected in the works of many thinkers that have contributed to contemplating this topic throughout the short history of cinema. In my next article, I have compiled a list of some of the key figures and texts in the field of film aesthetics, each accompanied with a brief overview, for those wanting to research this area of film studies further. You can read it here, and watch it here.

This article is also available as a video essay, which you can view below:

References

· Klevan, Andrew. (2018). Aesthetic Evaluation and Film. Manchester University Press.

· Lamarque, Peter. “History of Aesthetics.” Oxford Bibliographies in “Philosophy”. Oxford UP, last modified 25 Oct. 2012, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195396577/obo-9780195396577-0002.xml?rskey=MXEi0Y&result=12

· Noble-Olson, Matthew. “Film Aesthetics.” Oxford Bibliographies in “Cinema and Media Studies. Oxford UP, last modified 28 Sep. 2016, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199791286/obo-9780199791286-0212.xml

· Pappas, Nickolas. "Plato’s Aesthetics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/plato-aesthetics

· Shelley, James. "The Concept of the Aesthetic", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/aesthetic-concept/