In the Mood for Love: Nostalgia and Cinema

This essay analyses the parallel between nostalgia and cinema forged by Wong Kar-wai’s “In the Mood for Love”.

‘He remembers those vanished years.

As though looking through

a dusty window pane,

The past is something he could see,

but not touch.

And everything he sees

is blurred and indistinct.’

These translated words form the final intertitle before the enigmatic denouement of Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000) [1]. They follow the final scene featuring Mr Chow, played by Wong’s frequent collaborator Tony Leung Chiu-wai, whispering an inaudible secret into a hole carved out of the ancient stone walls of the Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia. In many ways this scene is distinct from the languorously nostalgic tale of fleeting moments, missed opportunities, and unrequited love, that constituted the preceding scenes. For one, the Cambodian location is removed from the dominant setting of colonial Hong Kong, as well as the brief Singaporean sojourn, that feature earlier in the film. The temple complex is captured from a variety of angles, including expansive wide-shots, and is bathed in sunlight: a welcome respite away from the claustrophobic interiors and narrow streets of Hong Kong that hardly ever see the light of day in the film. And, second, the scene takes place several years after the main events of the film transpired. As such, this scene effectively functions as one of distanciation: at once relegating all prior scenes to the past, and repositioning them as memory. Indeed, Wong has said as much, stating that he decided on ending the film in Cambodia so as to provide ‘a distance from the incidents’, he continues: ‘We can look [at] the whole [thing] from a distance, to provide another level’ (“Interview”, see below).

These ‘incidents’ that Wong is referring to entail the restrained romantic attraction that develops between Mr Chow and his neighbour, Mrs Chan, played by another of Wong’s frequent collaborators, Maggie Cheung. This attraction develops after the realisation that their respective spouses are having an affair with each other, and during their consolatory meetings that ensue. Yet, they vow not to ‘be like them’, and confine their relationship to apparently platonic parameters: the success of this vow remains ambiguous. Whilst, their feelings for one another are never explicitly consummated within the film, there are certain scenes that call into question the nature of their relationship. It has thus been widely inferred that the secret Mr Chow is disclosing before the ruins entails the details of these very incidents, these memories, that he has now been screened from by the passage of time, both within the film and by the film. The concluding intertitles, then, are not only referring to the process of memory, they are also referring to the process of cinema. This is an established analogy: both memory and cinema conceal their fragmentary, ephemeral, ontologies behind an impression of continuity and wholeness.

Yet, memory recollection alone is not quite adequate in describing the events of In the Mood for Love as it does not recognise the deeply nostalgic dimension of the film. In Screening the Past: Memory and Nostalgia in Cinema, Pam Cook has more accurately described In the Mood for Love as a ‘nostalgic memory film’ (5). In this book, Cook rethinks the criticism that regards nostalgia as ‘a simple device for idealising and de-historicising the past’, a common sentiment of Wong’s detractors (5). Instead, working with a definition of nostalgia as a ‘state of longing for something that is known to be irretrievable, but is sought anyway’, Cook views nostalgia as a process that ‘plays on the gap between representations of the past and actual past events, and the desire to overcome that gap and recover what has been lost’ (3-4). To Cook, the fantasy enacted in the process of nostalgia is useful in its capacity to reflect on ‘issues of memory, history, and identity’ (5). However, nostalgia is a common schema through which to analyse Wong’s films and is often utilised, as Cook goes on to exhibit, as a means to relate his films to broader sociohistorical milieu.

Alternatively, nostalgia can also be utilised to nuance the established analogy between memory and cinema in film studies. The process of nostalgia, understood as the futile desire to overcome an interval of elapsed time, also describes the ontological dilemma posed by cinema, a medium that projects a reality that was once present before the camera but is now absent before the viewer. The American philosopher, Stanley Cavell, writes of this dilemma in his seminal text The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film, saying: ‘The world of a moving picture is screened…It screens me from the world it holds––that is, makes me invisible. And it screens that world from me––that is, screens its existence from me’ (24). At the heart of this ontological enigma, then, is a difficulty in disentangling the notions of absence and presence, and the inability to discern the status of the interval created between these two states: ‘…we don’t know how to think of the connection between a photograph and what it is a photograph of’, Cavell writes (18).

In this way, overcoming and consolidating the connection or interval between two versions of reality is a process inherent to both cinema and nostalgia. As such, this essay seeks to mine this analogy through the analysis of In the Mood for Love, a film that displays an acute awareness of both processes. In particular, this analysis will focus on Wong Kar-wai’s use of 1) framing, 2) repetition, and 3) music and motion to forge this parallel.

I. FRAMING

The form of In the Mood for Love poses a perceptual case to be investigated and solved. In collaboration with cinematographers Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping-bin, Wong’s use of framing is strategic about what is disclosed and withheld from the viewer. The spaces utilised across the course of the film primarily feature the dislocated interiors of a tenement building, a restaurant, two office spaces, a hotel room, and an outdoor noodle stall, connected via a network of equally dislocated corridors, narrow streets and stairwells. As many commentators have noted, these spaces are captured within conspicuous mise en abyme, or frame-within-a-frame, compositions that are often shot through doorways and windows, or littered with objects in the foreground and around the edges of the frame.

Mise en abyme compositions are a common self-reflexive device that draws attention to cinema’s inevitable framing, and therefore proscription, of reality. As Cavell writes, ‘The implied presence of the rest of the world, and its explicit rejection, are as essential in the experience of a photograph as what it explicitly presents’ (24). Wong consistently harnesses the rupture in spatial continuity occasioned by the frame to serve multiple purposes. Firstly, the film’s restrictive framing effects a claustrophobic rendering of space that at once mirrors the stifling living conditions in Hong Kong, the emotional and romantic restraint of the two protagonists, and the entrapment of their predicament. And, secondly, the compositions are used to police the exposition encapsulated in each shot, demarcating the absence and presence of certain characters in such a way that causes confusion over their identities.

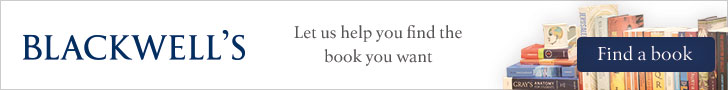

An example of this can be observed early in the film, soon after the two protagonists and their respective spouses have moved into the tenement building. A sequence begins with a shot tracking the mid-section of a woman, which reframes into a static long-shot, as she walks towards a room wherein a group are gathered playing, what appears to be, Mahjong (Figs. 1-2) [2]. The woman goes to sit down next to a man, both facing away from the camera, which is voyeuristically peering in from its static station outside the doorframe (Fig. 2). From behind, the man resembles Mr Chow: the only principle male character introduced thus far. If so, it would seem that the woman is Mrs Chow, owing to her intimate proximity to the man. Yet, the sultry entrance of a second woman into the frame, and then room, quickly destabilises this assumption when the seated woman turns to let her pass, revealing herself to be in fact Mrs Chan (Fig. 3).

The scene continues as Mrs Chan stands to let Mrs Chow pass leftward behind the doorframe and out of view (Fig. 4), from where Mr Chow then emerges, replacing his wife in centre frame (Fig. 5). This not only confirms his own identity but also the man seated at the table, who can now be safely assumed to be Mr Chan. Like cascading layers of visual knowledge, set to the sumptuous tune of Shigeru Umebayashi’s desirous strings, this scene continues to frame and then reframe the facts of the film’s perceptual case. Much like the recollection of nostalgic memory, factual discernment in such parameters is akin to aiming at a moving target. The imbricated character blocking of this scene speaks to the double interchangeability of the quartet, a kind of marital mitosis, that finds its full expression in the protagonists’ re-enactments later on.

Necessarily, the interval between presence and absence in cinema not only manifests between the two disparate realities of that photographed and that embodied by the screened viewer, but also at the edges of rupture imposed by the frame to the continuity of that reality it encloses. Peter Brunette correlates this explicit discontinuity of reality by framing in the film to a ‘motif of the impossibility of whole vision and complete understanding’ (99). Such a motif is suited to emulating subjective experience, especially as witnessed from a distance, as in nostalgic memory. Wong himself draws this phenomenological parallel when he explains that he wanted to construct compositions that emulate the restricted viewpoint of a child, namely his own at five years old (“Interview”). It is not a coincidence that the film features an exiled Shanghainese community in 1960s Hong Kong. This is the era and demographic that Wong occupied as a young boy, newly emigrated to the former British colony (“Interview”). The director is quite literally, then, reconstructing the sights and sounds of his childhood, with the process of filmmaking serving as a means of recollection and, as Carla Marcantonio argues, ‘preservation’.

Altogether, Wong’s use of restrictive and layered framing speaks to the nostalgic difficulty in recalling the past, and the cognitive leap thus required to overcome this elapsed time. Meanwhile, the emphasis placed on the frame foregrounds the gulf between what is captured and what is not, and reminds us that a similar process of overcoming in cognition is required of the cinematic viewer to reconcile this discontinuity.

II. REPETITION

The congested, layered framing of the interior settings dislocate the shots from any broader spatial contextualisation. Like a dream or hazy memory, they are suspended in abstraction. Even the network of corridors, narrow streets, and stairwells, that connect these dislocated interiors are themselves altogether unplaceable and anonymous. The looping repetition of action that unfolds in these abstracted spaces likens interior space to nostalgic memory. Paul Arthur notes this parallel made by In the Mood for Love, writing that Wong’s ‘narrow passages and cloistered chambers in which most of the action takes place are subtle, if by now rather familiar, tropes for the labyrinthine quality of the mind, its ceaseless movement along the same unending pathways of remembered experience’ (41). Wong reinforces this parallel by using montage to frustrate the continuity of the narrative in order to emulate the futile repetition of attempted recollection. This is a strategy deployed throughout the film, and a particularly potent example is observable once Mr Chow and Mrs Chan begin to speculate on how their spouse’s affair came to be by acting out possible scenarios.

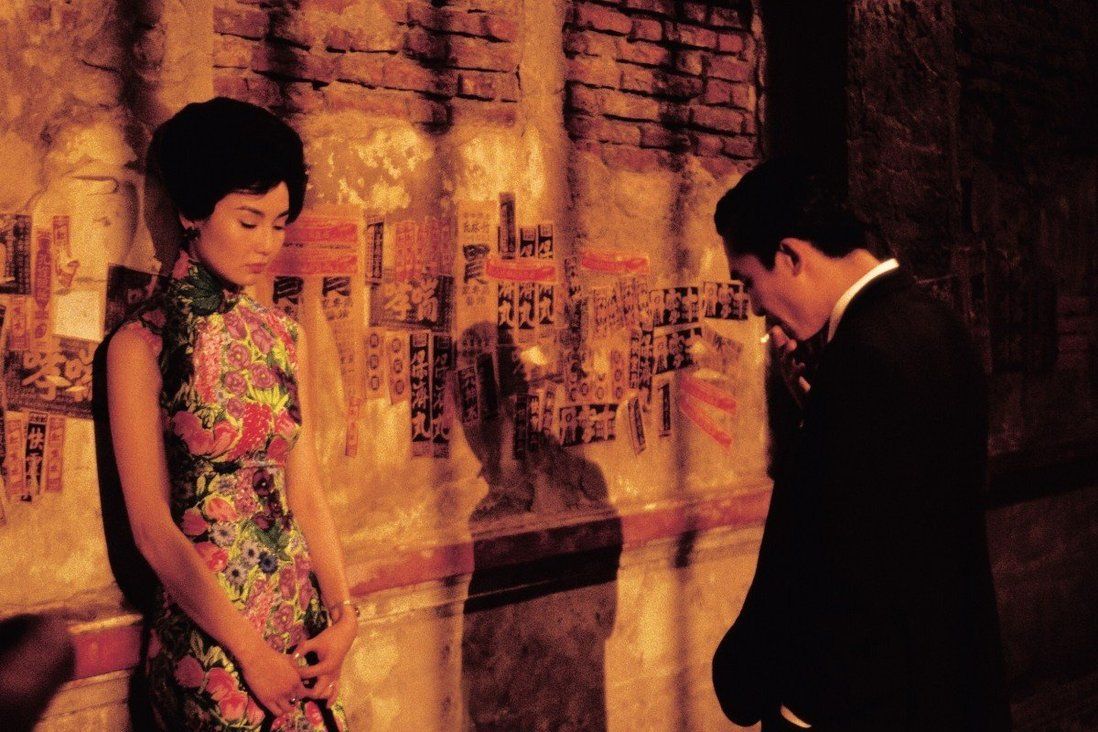

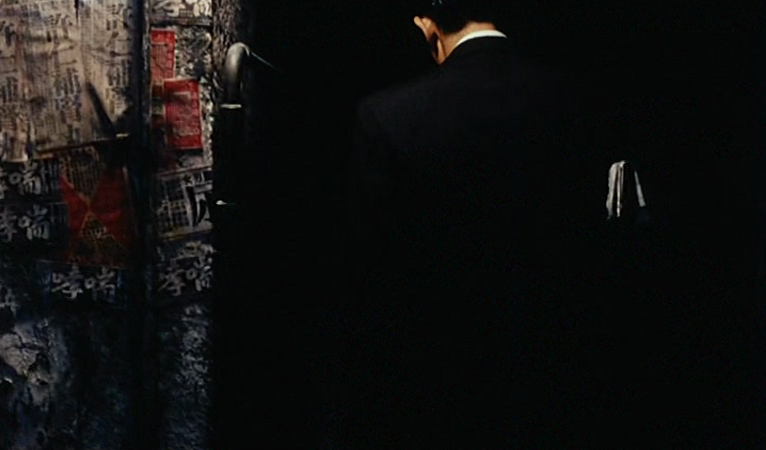

The first of these rehearsals takes place outside, on an evening walk down one of those anonymous decaying streets that the film features [3]. The sequence begins with a leftward track along a decrepit wall, on which two shadows are cast: quite literally foreshadowing the protagonists’ entrance into the frame (Figs. 7 - 9). In fact, the shadows not only cue the imminent presence of Mr Chow and Mrs Chan as stand-in actors might, but they also evoke the established absence of their respective spouses. Indeed, the reality of their spouses’ affair is made present in their explicit absence throughout the film. Necessarily, the protagonists themselves are removed from the presumably past (and present and future) liaisons of their spouses and, as we shall see, they try desperately to recover this absence in their speculative re-enactments, just as memory (and fantasy) does in its distortions.

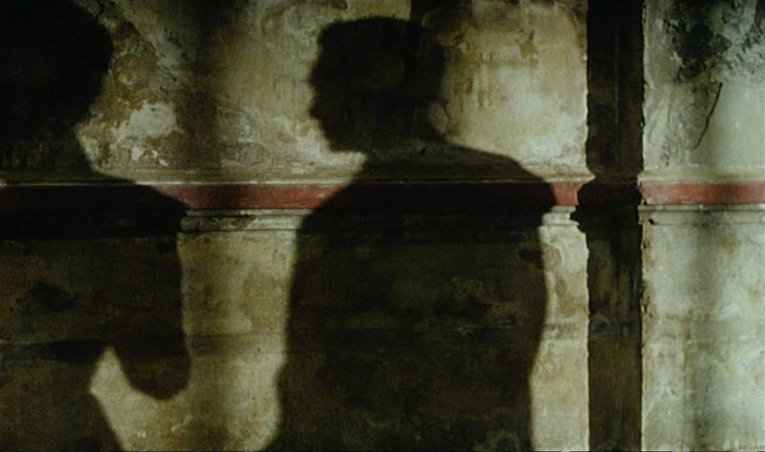

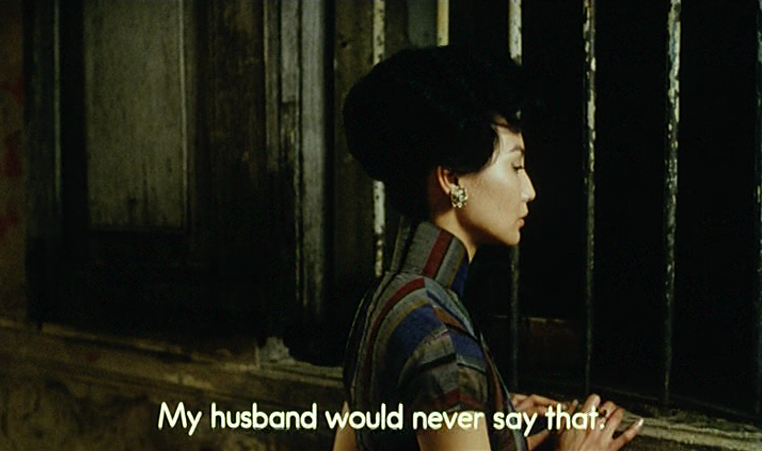

As their shadows fall off the wall like a muted clapperboard cuing the start of the scene, Mr Chow and Mrs Chan enter the frame and begin their first performance. Mrs Chan leads with her ring-finger, a veneer of social propriety that again graphically reminds of her absent husband and, like the shadows on the wall, an almost spectral tethering to him. She then proceeds to deliver her lines, although the performative aspect of the scene is not immediately obvious. ‘It’s late…won’t your wife complain?’, she says. Mr Chow responds that ‘she’s used to it, she doesn’t care.’ A similar question is posed vice versa, receiving a similar response. Mr Chow then proposes, ‘Shall we stay out tonight?’, and a mid-shot of their midsections reveals Mr Chow subtly grabbing Mrs Chan’s hand, qualitatively continuous with the intention of the proposal (Fig. 10). Breaking character under the pressure of this gesture, Mrs Chan turns towards a wall with barred spaces for windows, retaliating: ‘My husband would never say that’ (Fig. 11). It is here that the performative artifice of their conversation is first exposed.

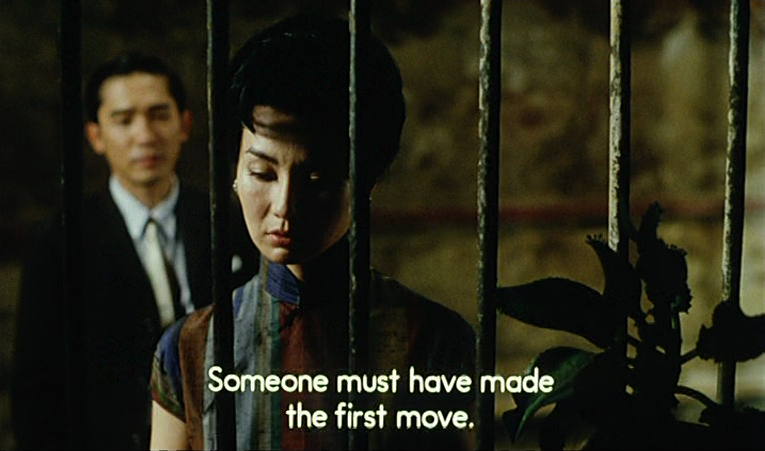

Once the performance is recognised as such, the characters are relegated behind bars in a reverse two-shot as moral propriety assumes its grasp. Harkening back to the interchangeability of the quartet in the earlier Mahjong scene, this sequence doubles as the instigation of the protagonists’ future romantic attraction and, by extension, potential affair to which their spouses are, likewise, now absent from. In this way, the bars graphically incriminate Mr Chow and Mrs Chan for the exact same marital crime they suspected of their spouses. Filmed from behind these bars, Mr Chow then justifies his advance: ‘Someone must have made the first move…who else could it be?’ (Fig. 12). Considered from Mr Chow’s future point of view, this line not only refers to his fruitless attempt to recover the reality of his wife’s affair, but it also suggests his inability to discern how his own illicit romance with Mrs Chan began.

Indeed, unable to complete the scene, this line prompts the first repetition of the same sequence. It is here that montage is put to use as a tool to emulate nostalgic recollection, the abrupt cut emphasising the frustration of this oftentimes obsessive process. As we are brought back to the beginning of the scene, the leftward track now assumes the function of continual rewind. This time, the camera passes behind intermittent stretches of solid wall, and barred spaces that vertically extend the height of the frame. The former creates momentary black frames internal to the one shot (Figs. 14 and 17), and the latter divides the composition into vertical fragments (Figs. 13, 15, 16, 18). Together, these two graphic qualities mimic a perforated film strip, magnifying the fragmentation that occurs at a cellular level in cinema, in a way that reminds one of Eadweard Muybridge’s galloping horse. By making this allusion, Wong relates the process of overcoming in cognition required to consolidate these fragments, these instances of presence and absence, to the reconciliatory desire of nostalgia.

III. MUSIC AND MOTION

I would like to end this essay with an analysis of the sequences that are notably accompanied by a musical cue and set to slowed down motion. In their pronounced attempts to cling to the transient moments of fleeting connection contained within them, these sequences are especially useful in rethinking the alignment of nostalgic memory and cinema. Structurally, they bridge the other disparate scenes dispersed throughout In the Mood for Love, and largely take place in the network of corridors, stairwells, and narrow streets featured in the film. Although, the earlier Mahjong scene also takes up the same bridging function, as do the later scenes taking place in Mr Chow’s hotel room. These sequences make the futile process of temporal reconciliation inherent to nostalgia and cinema perceptible by staging an audio-visual insurrection against the finality of the fleeting moment memorialised, both by the mind and camera.

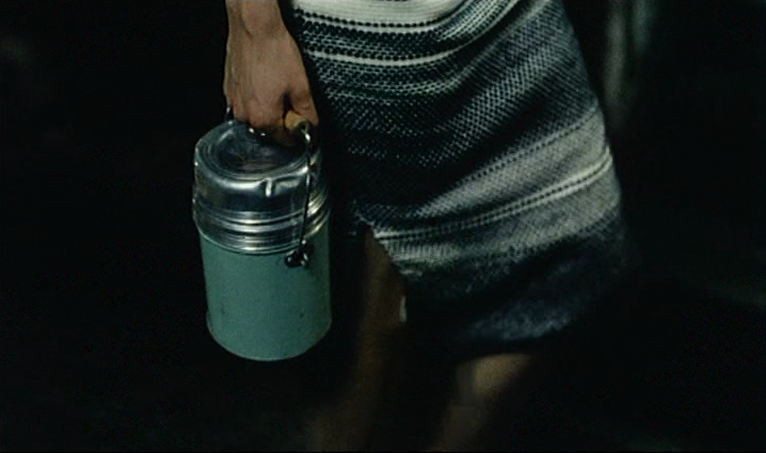

An example of this can be seen in Mr Chow’s and Mrs Chan’s first few uncoordinated encounters during their nocturnal pilgrimages to the outdoor noodle stall [4]. These sequences are abstracted from their immediate structural surrounds: they effect a rupture in spatial, temporal, and narrative, continuity. In this sense, they represent an interval in narration. They also deviate from the usual frequency that images occur in film by adopting a higher frame rate to produce a slow-motion rendering of space and time. Necessarily, as more frames are required––closer to 60 frames-per-second, rather than the usually naturalistic 24 frames-per-second––to achieve this rendering, the time elapsed between each frame is shortened. What can therefore be seen in this cinematographic stricture is the magnified attempt to overcome the fragmentation inherent to cinema. In other words, these sequences pose a mounting protest against the cruel impermanence of celluloid, and the life therein impressed by light.

Most notably, these lethargic encounters are set to Umebayashi’s non-diegetic tune ‘Yumeji’s Theme’ as the principle characters saunter down the stairwell to the perspiring pit that is the noodle stall below, each time dipping their feet into that well of frustrated eroticism (Fig. 19). Two general trends characterise the theme’s plaintive melody: The pizzicato plucking of the string section––evocative of a ticking clock, and a sonic measurement of passing time––and the forlorn drags of the lead violinist’s bow, infusing an exclamation against this sonically inscribed transience. In further revolt, the camera lingers on the couple’s intersection and then, once dispersed, on the crumbling wall behind them rendered palimpsestic with posters and, indeed, witnessed transience (Fig. 24). As with the rehearsal scene, architecture is used here to commemorate the passage of time in a way that memory cannot, its decay more enduring than our own ephemeral corporeality and the faulty inconsistencies of recollection.

Altogether, the distinct combination of the languorous motion and the longing theme amplifies the qualitative continuity otherwise established in the film. The camera clings desperately to gesture, place, objects, and atmosphere, as if to retrace the taciturn steps of the protagonists in search for some way to materialise the evasive romance between the two. In this way, these sequences epitomise nostalgic desire, and imbue the rest of the film with this same intoxicating impression. This essay has shown that this nostalgic impression is an apposite aesthetic strategy to wrestle with the ontological complexities of cinema. Both are predicated on an interval between different moments in time, and both instigate a process of overcoming in cognition to reconcile this discrepancy.

The ultimate inefficacy of this process reminds us of the incompossibility of linear time, and the human inability to conceive of this temporality any differently. But, in doing so, it also reminds us that, precisely owing to its linearity, cinema’s philosophical profundity lies in its unique ability to ontologically materialise and integrate this dilemma, and attempt to overcome it, even if these attempts are as evanescent as the fleeting moment.

NOTES

[1] Quotations themselves, all the intertitles that In the Mood for Love feature originally appear in Liu Yichang’s 1972 novella, Intersection, which also happens to be the (loose) source material for the film itself (McElhaney 371).

[2] Sequence timestamps: 04:05 – 05:09

[3] Sequence timestamps: 28:49 – 30:34

[4] For example, see the sequences of the following timestamps: 13:16 – 14:48 (Figs. 19 – 21) and 22:17 – 23:51 (Figs. 22 – 24).

REFERENCES

· Arthur, Paul. “In the Mood for Love.” Cineaste, vol. 26, no. 3, 2001, pp. 40 – 41.

· Brunette, Peter. Wong Kar-wai. U of Illinois P, 2005.

· Cavell, Stanley. The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film. Harvard UP, 1979.

· Cook, Pam. “Rethinking Nostalgia: In The Mood for Love and Far From Heaven.” Screening the Past, Routledge, 2005, pp. 1 – 19.

· Marcantonio, Carla. “In the Mood For Love.” Senses of Cinema, no. 56, Oct. 2010.

· McElhaney, Joe. “Wong Kar-wai: The Actor, Framed.” A Companion to Wong Kar-Wai, edited by Martha P. Nochimson. Wiley Blackwell, 2016, pp. 357 – 379.

· Wong, Kar-wai. “An interview w/ Wong Kar Wai on IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE (2000)” Youtube, uploaded by Eyes on Cinema, 30 Sep. 2014.

FILMS

In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000)

Note: This article contains affiliate links.