Film Sound: Michel Chion's "Acousmêtre"

This article provides an overview of Michel Chion's concept of the 'acousmêtre'.

Born in 1947, Michel Chion is a French film theorist and composer of experimental music. He has published several seminal books on the relationship between image and sound in film––such as Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, The Voice in Cinema, and Sound in Cinema––as well as numerous studies of individual directors and films [1].

In his books on sound, Chion developed a lexicon that imparts a precise understanding of image-sound relations, with one of his most notable concepts being the ‘acousmêtre’: the topic of this article, which will proceed by providing an overview of the concept and analyse a number of examples from films that display different variations of this phenomenon.

Alternatively, you can also watch the video essay version of this article below:

What is an Acousmêtre?

The term ‘acousmêtre’ is constituted by an amalgamation of the word ‘acousmatic’, which refers to sound that can be heard without the source being seen, and ‘être’, the French verb ‘to be’ or ‘being’. Altogether, an acousmêtre refers to a special type of character in cinema that exists as an offscreen voice that can be heard but not seen. Distinct from a detached narrator commonly found in the documentary genre, Chion clarifies that an acousmêtre is always implicated within the unfolding action despite its unlocatable source (Audio-Vision, 129) Further to this, Chion identifies four unique qualities that the acousmêtre possesses:

First, the acousmetre has the power of seeing all; second, the power of omniscience; and third, the omnipotence to act on the situation. Let us add that in many cases there is also a gift of ubiquity—the acousmetre seems to be able to be anywhere he or she wishes. These powers, however, often have limits we do not know about, and are thereby all the more disconcerting. (Audio-Vision, 129 - 130)

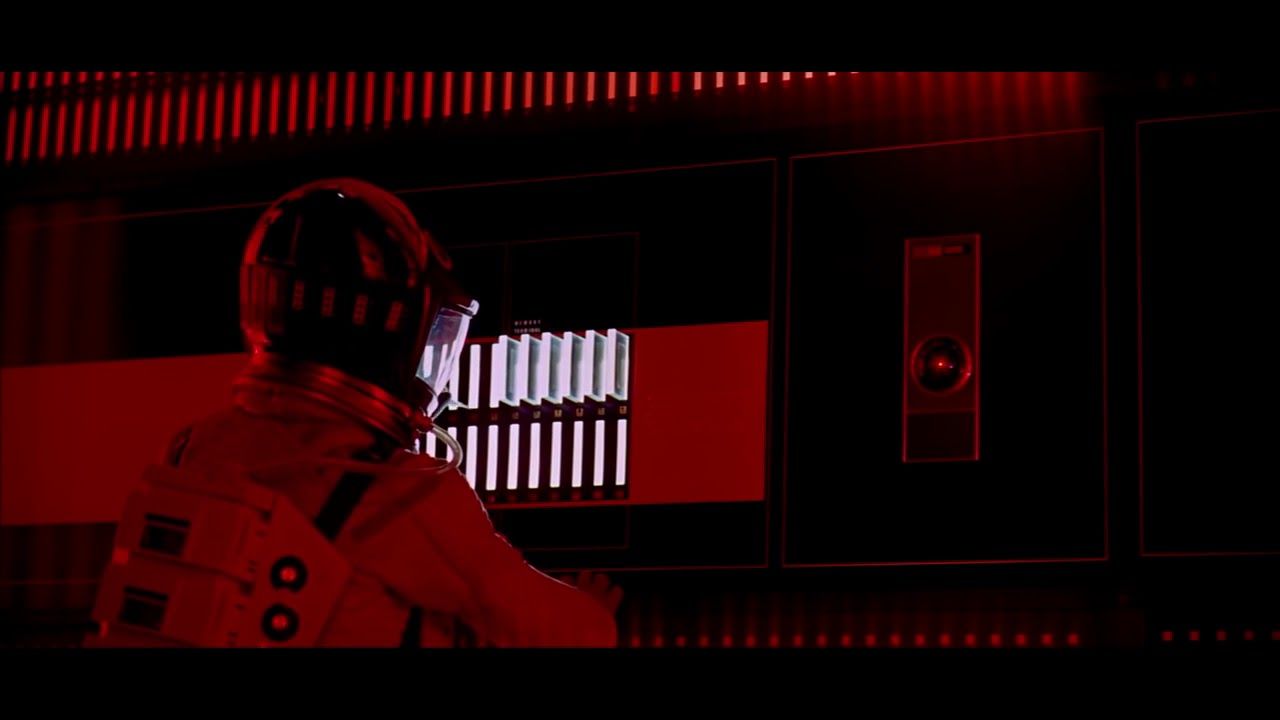

A classic example of an acousmêtre is HAL 9000, the murderous artificial intelligence that controls the systems of the Discovery One spacecraft in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The qualities that Chion attributes to the acousmêtre are, at first, epitomised by HAL and asserted through his machinic voice of unnerving equanimity: the computer is able to see all that happens on the spacecraft, he possesses an intellect that surpasses the capabilities of humans, he has the ability to control the systems of the spacecraft, and his presence appears to pervade the profilmic space.

Another commonly cited example of this phenomenon is the character of the wizard in Victor Flemming’s The Wizard of Oz (1939) who is, at first, also granted a powerful presence through the use of a disembodied voice. Although, this presence is quickly divested of the qualities Chion identifies upon the revelation that a mere man behind a curtain is the source of the voice. This process, the visualisation of a character that was at one point an acousmêtre, is what Chion terms ‘de-acousmatization’ or ‘visualised sound’ (Audio-Vision, 72, 130-131). In other words, when we see that the wizard is a man like any other, as well as sense the gulf between his human voice and the artificially amplified voice that he tried to project as an acousmêtre, the perceived power of the latter completely deflates.

Chion accounts for this deflation by pointing out that when the source of a sound is visualised it takes on a certain, and therefore limited, form. On this process, Chion writes that visualised sound is ‘an “embodied” sound, identified with an image, demythologized, classified’ (Audio-Vision, 72). In the case of the wizard, this embodiment is quite literal. Seeing the sound of the wizard take on a human form reminds one of all the vulnerabilities and frailties of the human condition, which ultimately undermines the projected transcendence of the acousmêtre. If we consider the initial example of HAL, however, complications arise.

Hyper-Acousmatization

The partial visualisation of HAL in the form of the searing red lens does little to diffuse his oppressive presence. As the film unfolds, the astronauts make the mistake of only comprehending HAL as an ear, as a being that only gathers information sonically, rather than the ear and eye that he actually is. In fact, HAL’s ability to use visual information, namely lip-read, only functions to amplify the powers signalled by his voice.

Like a dome CCTV camera, HAL’s concave, lifeless, eye contains no emotion or direction: there is no way to discern what exactly he is looking at, which fosters the intimidating impression of being, quite literally, an all-seeing eye. This perceptual ambiguity is further exacerbated by the lack of emotion conveyed by HAL’s eye, and shrouds his motives and abilities in uncertainty.

It appears, then, that when the ‘embodiment’ of an acousmêtre comes in a machinic, or at least ambiguous and unemotive form, the process of de-acousmatisation does not occur, but rather the exact opposite. Instead of deflating the powers once asserted by the acousmêtre, the indistinct visualisation of such only acts to amplify those qualities further in a process that I am calling hyper-acousmatization.

Altogether, the interval that emerges between image and sound is something unique to cinema, and the ability to manipulate the relationship between these two dimensions of the medium offers the filmmaker endless creative possibilities. This video has shown that the acousmêtre, a voice character that can be heard but not seen, is but one of these. Whether the source of that character is a machine or a human or something else entirely, this sonic phenomenon identified by Chion demonstrates how the voice, and indeed sound more broadly, can be used to great effect in cinema.

Notes

[1] For instance, Kubrick’s Cinema Odyssey, David Lynch, Eyes Wide Shut, and The Thin Red Line.

References

· Chion, Michel. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. Edited and translated by Claudia Gorbman, Columbia UP, 1994.

Films

2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

Her (Spike Jonze, 2013)

The Wizard of Oz (Victor Flemming, 1939)

Affiliate Links

This article contains affiliate links to Blackwell's and Amazon.